The criminal mind

What is the potential for neuroscience in the courtroom?

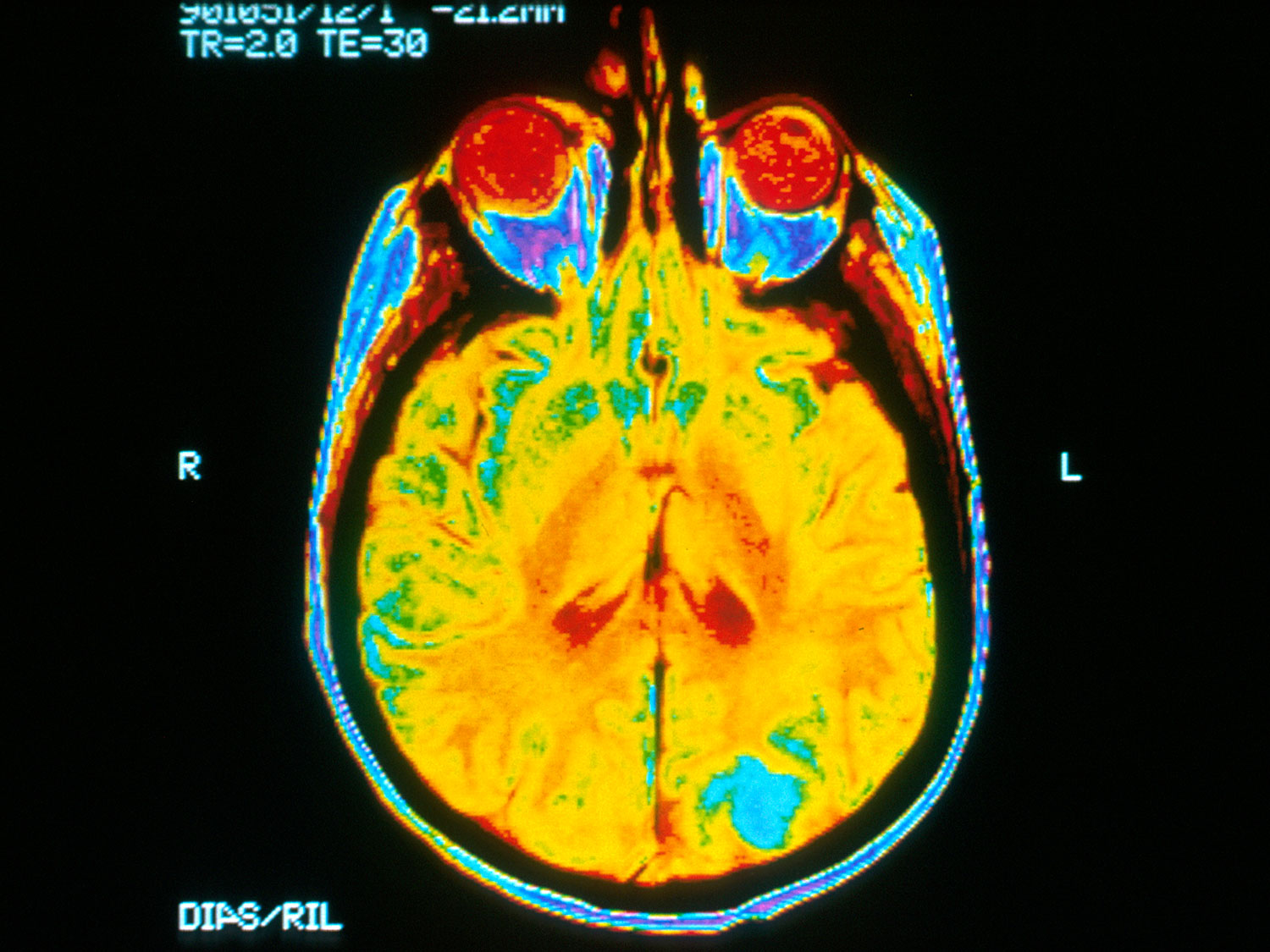

Some neuroscience techniques have made big strides into the courtroom recently. fMRI monitors blood flow and oxygen levels to create a picture of brain activity in real time – the theory goes that if we know which thoughts or emotions are represented by certain patterns of activity, we can ‘see’ these in a defendant’s brain.

Kent Kiehl at the University of New Mexico has scanned the brains of over 1000 psychopaths and identified abnormalities that characterise the disorder. He has now taken this evidence onto the stand for the first time, and testified that the brain of serial killer Brian Dugan fits this mould. His lawyer hopes this will convince jurors that he could feel no remorse for his crimes, helping him avoid the death penalty. ‘Brain Fingerprinting’ uses a headband with sensors to detect the P300 brain wave, which occurs when we recognise something. This has also been admitted in US courts, sometimes as evidence of whether suspects have seen specific details of a crime scene before.

These recent advances hint at the massive potential for neuroscience in law, and are fuelling discussion of its potential uses, raising some uncomfortable issues. If you’ve seen your share of cop dramas, you know a suspect always gets ‘the right to remain silent,’ but the use of brain scanning or an infallible lie detector could compromise this right. Diminished capacity defences often attempt to blame actions on brain differences, but the point at which an abnormal brain activity takes away personal responsibility may become harder to define. Of course in reality, all behaviours from tooth brushing to terrorist plotting ultimately stem from brain signals. You can get in trouble now for building a bomb, even if you don’t get the chance to set it off. If we could ‘see’ an intention to kill, would that really constitute a crime?

These are fascinating but far-fetched possibilities; a sci-fi writer may send a shiver with tales of thought crime, free will and rights abuses, but a sceptical neuroscientist or a lawyer would be more likely to highlight the painstakingly slow process of research verification and admissibility of evidence. The path to the courthouse for neuroscience is likely to be paved with technical, bureaucratic and moral obstacles.

In criminal cases, decisions are black and white, with little room for revision. There are processes for admitting scientific evidence in court, but these need development to accommodate new types of evidence. Firstly, to establish what level of confidence in a technique is enough, and secondly to educate lawyers, judges and jurors about what this evidence can and cannot tell them. No prosecution lawyer will be parading a catalogue of your ill intentions any time soon, but it is certainly worth keeping a close eye on development in this area (as the lawyers surely will be). Just in case.

Share

Tweet this Share on Facebook