Notes from the Forum d’Avignon Ruhr

Local and European government representatives attempt to decode urban innovation in Germany.

What is it that makes innovation flow in a city? This was the principal question of our Liquid City salon last year and is the holy grail for urban developers. For governments, the line of thinking goes: if you can fully understand economic innovation, then you might manufacture industrial growth to create boomtime all of the time. Of course, Silicon Valley is the template for a modern innovation capital, and governments all over the world want a piece of the action: Skolkovo in Russia, Tel Aviv in Israel, Espoo in Finland. There have been a few qualified successes and many more abject failures as countries imitate their own ‘Silicon’ innovation hotspots.

AtLiquid City we spoke to Eric van der Kleij, who was at that time David Cameron’s principal salesperson for the ‘Tech City’ project in Queen Elizabeth Park, Stratford (formerly known as the Olympic Park). He talked a good game, but it was hard not to sense a disconnect between his political platitudes and the probing questions of the many entrepreneurs in the audience, who were hungry for the red flesh of policy. Meanwhile, his enthusiasm for creating a safari park for tech corporations, situated a full five miles away from Europe’s fastest growing digital economy, suggested the British government was struggling to understand the historical accidents that transformed Old Street roundabout into a European outlier.

At the salon we came to the conclusion that innovation is principally caused by the collision of ideas and people connecting across a network. The process is accelerated by the proximity and density of its nodal points – that is, people living and working close together, and in large numbers. Therefore, we learned that diverse subcultures – from punks to tech nerds to visual artists and different ethnic and age groups – play a powerful role in economic development, creating information spillovers that soon see forces of economic geography kick in to create positive feedback loops. More trade, more bars and streetlife, more sex. That sort of thing. And it was the creative economy that formed a social environment hip tech entrepreneurs wanted to buy into, whether it was Palo Alto PC coders day tripping their way through Haight-Ashbury in the 1970s, or early 20s geek entrepreneurs hanging out near the White Cube in Hoxton.

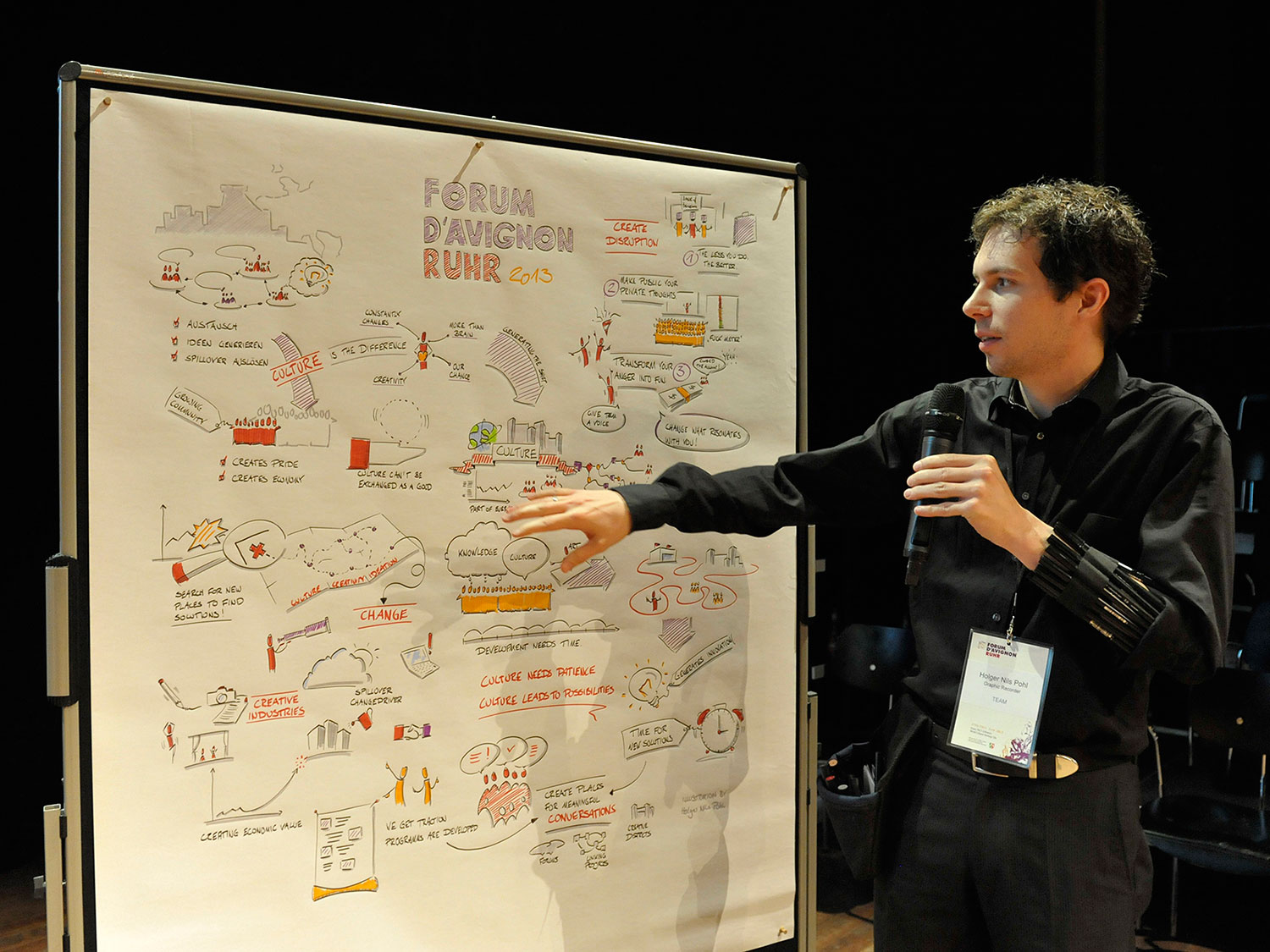

That’s why we found it fascinating to attend the 2013 Forum d’Avignon Ruhr in Essen, Germany earlier this summer. The Forum d’Avignon is a festival that bills itself as ‘a European Laboratory for the economy and culture’ with a particular focus on cultural spillovers. Bringing together leading creative entrepreneurs from across Europe, corporate bigwigs from Google, Sony and BMW, and some of Europe’s most powerful policymakers, the event is principally an advertisement of the cultural and economic potential of the Ruhr region in North-West Germany. Historically an industrial powerhouse, the Ruhr region is nevertheless considered a puny relation to the cultural behemoth that is Berlin. But as its heavy industries have declined, the government of North-Rhine Westphalia has sought to promote its rising arts and media economy, planning creative quarters in deindustrialised facilities and turning coal collieries into gallery spaces.

So Forum d’Avignon Ruhr is an important powwow for the creative economy in Germany, and for Europe more generally, as it seeks to establish a dialogue between creative producers and the national and supra-national policymakers who control the macro conditions they work under.

Amongst all of the panels in a long day at the Pact Zolleverein artistic centre, the most intriguing involved the politicians responsible for urban planning in the region, and for managing the funding mechanisms supporting creativity in their constituencies. To put it kindly, they came across as primary school teachers addressing an MA class. Description of policy was essentially non-existent, and cloudy groupspeak was the order of the day: each of the politicians agreed upon the universal positivity of ‘culture’, ‘art’, ‘knowledge exchange’, ‘cultural spillover’ and ‘innovation’. The conversation reached some kind of zenith when Dorata Nigge, billed as the ‘Head of Unit, Culture Policy and Intercultural Dialogue for the European Commission (EC)’ spoke:

“I dream,” she said, “of creative bureaucracy.”

Curious as to how a system of practise commonly associated with doing nothing might be honed into something even less conclusive, I tracked Nigge down for an interview after her appearance. Despite professional nomenclature that would make a Welsh town planner blush, she has an influential role shaping the EC’s cultural programme, into which an estimated €1.8 billion will be invested between 2014 and 2020.

The EC typically funds creative projects in the €100,000 to €700,000 bracket and the application process is famously labyrinthine, requiring multiple collaborators from three or more European countries. So the critical question for Nigge was, who can be bothered to apply apart from salaried academics with an inexhaustible appetite for red tape?

“I will say that training is very important for pitchers,” she said.

Nigge went on to deadbat a number of questions, before presenting a fig leaf. The EC proposes to partner with banks to offer a subsidised loan (in wonk parlance, ‘a special guarantee’) to creative entrepreneurs. The scheme should launch in 2014, and augment the EU’s existing cooperation programmes and ‘Erasmus’ student exchanges.

Asked to explain how any normal creative enterprise might access EC funding, Nigge excused herself, saying that she had not agreed to speak for more than 15 minutes.

Unfortunately, the truth was all too apparent. The stated purpose of the EC culture programme is help Europe’s creative sectors with funding and encourage international cooperation – the ‘cultural spillovers’ that cultivate innovation and are beloved of public policy jargonistas. In reality, the EC Culture Programme is an enormous vanity project with nebulous outcomes. Despite huge investment, it remains internationally uncompetitive.

Its 2014 strategy document ‘Creative Europe’, embracing humour worthy of Franz Kafka, states that the EC will overcome the major challenges facing the European cultural sectors by formulating ‘new and refocused objectives and priorities’ and ‘simplified instruments’.

This kind of paralysed, vertically integrated ‘creative bureacracy’ is, of course, the exact opposite of what is required to stimulate creative businesses and accelerated interactions between diverse subcultures. In other words, they’re proposing more blah, less bars.

Germany is fortunate that it’s recent history of multiculturalism and immigration (10 million of the country’s 74 million population are of immigrant heritage) has seen an injection of ideas from Balkan, Soviet, Turkish and Polish subcultures. Situated to the north-east of the country, Berlin has the highest proportion of migrants, which in part accounts for the city’s rich cultural scene and creative economy. Berlin has subsquently experienced growth in more scientific industries, from information and communications tech, bio and green tech and medical engineering. But all of this is an accident of location, and of the uncoaxed interactions between diverse cultural, ethnic and industrial subcultures, who spend their time living and working in close proximity to one another.

As ever, politicians talk up the benefits of developments like this but their influence on them is minimal. Berlin is a successful innovation hub, but can another region such as the Ruhr hope to emulate it? And can anything be done to engineer a creative economy that attracts other innovative industries – and growth?

I spoke to many many leading figures from Germany’s creative industries at the Forum d’Avignon Ruhr, and their answer to this question was unanimous: fund the coaches of creative activity.

“Creative mentors are ignored by these people,” said Alexander Koch, co-founder of the KOW gallery in Berlin. “Yet they are the true patrons of undiscovered artists and innovators.”

It’s a simple prescription. Give money to the people who currently receive no support whatsoever, yet who prop up the entire cultural edifice by encouraging the makers and creators of tomorrow. Without professional encouragement, support and funding, the top creatives argued, innovation withers and entrepreneurs go elsewhere.

Photography by Vladamir Wegener

Share

Tweet this Share on Facebook